What

Series of three quick, bedside, physical exam maneuvers that can potentially rule out a central cause of vertigo

Hi for head impulse testing, or head thrust testing.

N for nystagmus to remind you to look for direction-changing or vertical nystagmus

TS for test of skew.

Why

Nearly two-thirds of patients with stroke lack focal neurologic signs that would be readily apparent to a nonneurologist

Presence of all three “reassuring” exam findings suggests it can be ruled out with a 100% sensitivity for ischemic stroke in AVS while an initial MRI with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) had a 88% sensitivity

Who

Maneuvers used to help distinguish between central and peripheral vertigo in patients experiencing an acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) which is best defined as: rapid-onset vertigo, nausea and/or vomiting, gait unsteadiness, head motion intolerance, and nystagmus.

When

The patient must be experiencing continuous vertigo for the results to be reliably interpreted.

How

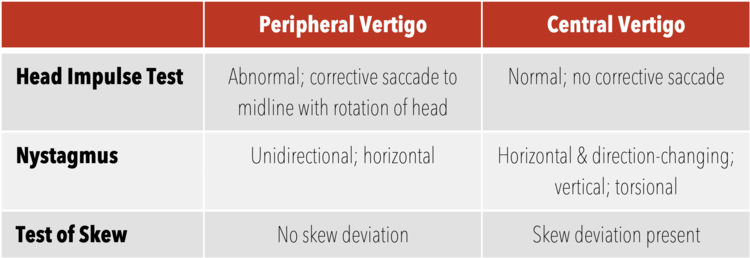

Head Impulse Test

Ask the patient to relax his/her head and maintain his/her gaze on your nose. Gently move the patient’s head to one side, then rapidly move it back to the neutral position. The patient may have a small corrective saccade. The head impulse test is positive (consistent with peripheral vertigo) if there is a significant lag with corrective saccades. If you can see the correction, it is abnormal. Compare this to the contralateral side; a difference in the speed of correction should be noted.

In acute vestibular syndrome, an abnormal result of a head impulse test usually indicates a peripheral vestibular lesion, whereas a normal response virtually confirms a stroke.

Abnormal exam rules in peripheral vertigo and thus rules out central vertigo if only unilateral

Video- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XpghlvnrREI&feature=youtu.be&t=665

Nystamus

Note if it is present in primary gaze (i.e. looking straight ahead) and or in lateral gaze. Unidirectional, horizontal nystagmus is reassuring for peripheral vertigo where as purely bidirectional, vertical or torsional can be consistent with central cause

The most common peripheral nystagmus, BPPV, in the posterior semicircular canal consists of a unidirectional horizontal nystagmus with a torsional component.

Test of Skew

Have the patient maintain his/her gaze on your nose. Alternate covering each of the patient’s eyes

Positive result will be the deviation of one eye while it is being covered, followed by correction after uncovering it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WAPaIMMsV_A

Summary

If the HiNTs exam is entirely consistent with peripheral vertigo (positive head impulse test, unidirectional and horizontal nystagmus, negative test of skew), then, according to the derivation paper, it is 100% sensitive and 96% specific for a peripheral cause of vertigo.

Use of HiNTs exam in the ED is currently controversial as the primary study was performed by neurologists in a partially differentiated patient population

likely has higher utility in the patient population in whom the clinician suspects a peripheral cause of their vertigo to rule out central cause and limit needless imaging

Limitations

Do not perform on any patient that has head trauma, neck trauma, an unstable spine, or neck pain concerning for arterial dissection.

Do not perform in patients with known severe carotid stenosis as it may embolize unstable plaque

Challenging to differentiate between catch up saccade and nystagmus

Patients with acute active AVS likely to not tolerate the testing

Patient must be awake and cooperative.

Essentially an awake “doll’s eye” that requires conscious fixation on an object. Cannot perform on mentally impaired or sedated patients

Not yet been validated by a large external group, let alone a large external group of emergency medicine providers.

In the study, exam performed by ophtho neurologists

References

Nelson, James A., and Erik Viirre. "The clinical differentiation of cerebellar infarction from common vertigo syndromes." Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 10.4 (2009): 273.

Kattah, Jorge C., et al. "HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging." Stroke 40.11 (2009): 3504-3510.

Tarnutzer, Alexander A., et al. "Does my dizzy patient have a stroke? A systematic review of bedside diagnosis in acute vestibular syndrome." CmAJ 183.9 (2011): E571-E592.