If you remember one thing from this post remember this: up to 50% of dislocations spontaneously reduce before presentation to the the ER - these patients are STILL at high risk for neuromuscular injury. Take a good history about the mechanism of injury, get a good exam, and follow the instructions below, to make sure you dont miss a popliteal artery or peroneal nerve injury!

Diagnosis of Knee dislocation:

up to 50% of dislocations spontaneously reduce before presentation to the ER, but that doesn’t mean a neurovascular injury didn’t occur during the dislocation

consider the mechanism of injury: motor vehicle accidents, other high velocity mechanisms (falls, downhill skiing, football) make dislocation more likely

in rare cases, low velocity injuries in the obese, or sudden twisting motions in athletes can also result in dislocation

knee exam should focus on appearance, integrity/stability of joint, distal perfusion, and evaluating for peroneal nerve injury

peroneal nerve provides ankle dorsiflexion, toe extension, and sensation to first dorsal web space

usually 3 or more major knee ligaments must rupture for the knee to dislocation, so any knee exam w/multi-planar instability should be a suspected dislocation that spontaneously reduced

Anterior dislocation is most common (50-60%) named for the direction of translation of the proximal tibia

Posterior dislocation is even more commonly associated w/popliteal artery injury

Diagnosis of complications, especially in a spontaneously reduced knee:

most common injury is popliteal artery injury

presence of pulses does not exclude injury to the popliteal artery

if missed, can end up with AKA (delay of pop artery repair beyond 8 hrs invariably leads to limb amputation)

this is a highly litigated injury

ruling a popliteal injury via “hard signs” requires an immediate vascular surgery consult

hard signs include absence of pulse, pale or dusky leg, parasthesias and paralysis, rapidly expanding hematoma, pulsatile bleeding, bruit or thrill over the wound

There is no physical exam sensitive enough to rule out popliteal injury!!

quality of evidence behind ABI is poor as well

Wills et al prospective study suggests that normal ABI + period of observation w/no change in exam is 100% sensitive combination for ruling out vascular injury

Standard angiography is the standard of care

CT angio with runoff is next best test in the ER - ORDER THIS if concern for vascular injury

Management of a currently dislocated knee:

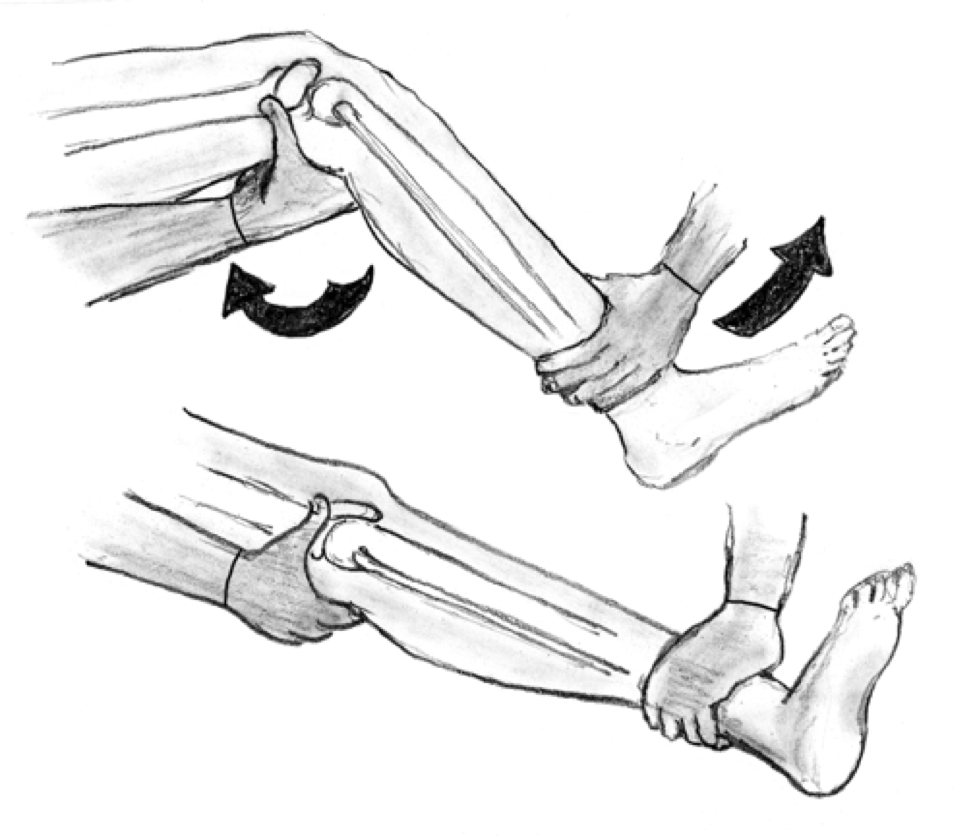

1. First and foremost the immediate reduction, and if neurovascular compromise exists – without radiographs.

a. Look for an anteriomedial skin furrow or “pucker sign” when the knee is extended – this signifies a posteriolateral dislocation, which are not reducible by closed reduction (require open reduction in OR).

a. Document neurovascular exam before and after reduction attempts

b. Initial approach should be application of longitudinal traction to lower leg (anterior dislocation may require additional lifting of distal femure, while posterior may require lifting the proximal tibia to complete reduction.

c. After reduction, the knee should be immobilized in a long leg posterior splint with the knee in 15-20 degrees of flexion

d. Again, these pts need either normal ABI with close monitoring and serial exams OR CTA to rule out vascular injury after initial reduction

References: