This week’s VOTW is brought to you by the UST~

A 9 month old female infant was brought into the Pediatric ED two days after a fall from a high chair. The infant vomited once after the fall but was otherwise acting normally since then. The patient was brought to the ED 48hrs after the fall for a boggy left parietal scalp hematoma. The patient had a normal physical exam apart from the hematoma. A POCUS was performed which showed...

Clip 1 shows an oblique disruption in the cortex of the skull, indicative of a fracture. The bones have an “overlapping” appearance. A hypoechoic hematoma is present overlying the fracture.

Image 1 shows the same fracture with relevant structures labeled.

Image 2 shows a cortical disruption in the skull of the same patient, but this one is a cranial suture

Sutures and fractures look the same! How do I differentiate them?

A suture can be followed all the way to a fontanelle.

Sutures are present symmetrically - scan the contralateral side if unsure

Fractures may appear irregular, jagged or displaced.

Sutures generally have an “end-to-end appearance” (image 2)- the cortex stops, there is a small space, and then restarts.

A fracture is likely to have an overlying hematoma.

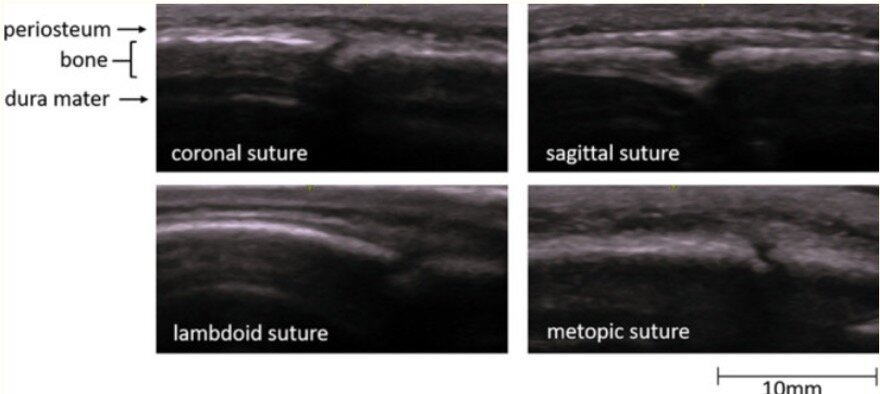

Image 3. More examples of sutures

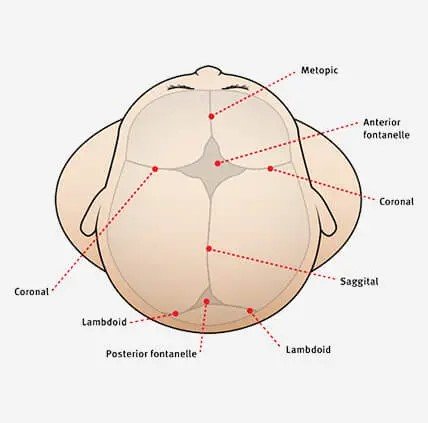

Image 4. A review of the anatomy of sutures and fontanelles

How to perform the study

have a parent or assistant stabilize the child’s head, especially if they are squirmy

use a linear high frequency probe and a lot of gel, especially if there is hair

warm up the gel (put the gel bottle in your backpocket) which might make it less uncomfortable for the patient

scan the area of swelling in two orthogonal planes and look for disruptions in the cortex

scan the area around the hematoma as well- the fracture may not be directly under the hematoma

Clinical Decision Making

There is limited data on the use of POCUS for diagnosing pediatric skull fractures.

When performed by EM Physicians, POCUS for skull fractures has sensitivities ranging from 67% - 100% and specificity of 85% - 100% (1)

The presence of a skull fracture increases the likelihood of intracranial injury by four-fold (2)

POCUS for pediatric skull fractures might be most useful in the borderline case- for example a child who has an occipital/parietal/temporal scalp hematoma but otherwise looks great in the ED. Using PECARN you decide that you would rather observe this patient than subjecting the patient to radiation +/- sedation. If you decide to perform a POCUS, the absence of a skull fracture might be reassuring to you (and the family) and support your shared decision to observe the patient. The presence of a skull fracture might raise your concern for intracranial injury and change your decision about imaging.

For a patient with a high pre-test probabiltiy for underlying pathology a negative POCUS should not be used a rule out test.

It might also be useful seeing a depressed or complex skull fracture as this may expedite imaging and specialist consultation.

More research is needed to define the role of POCUS in clinical decision making and how we might be able to integrate it with clinical decision rules like PECARN.

Happy Thanksgiving!

Your Sono Team

Alexandridis G, Verschuuren EW, Rosendaal AV, Kanhai DA. Evidence base for point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for diagnosis of skull fractures in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. 2022 Jan;39(1):30-36. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-209887. Epub 2020 Dec 3. PMID: 33273039; PMCID: PMC8717482.

Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al.. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study