Chapter 1: What dafuq is in an amp of bicarb?

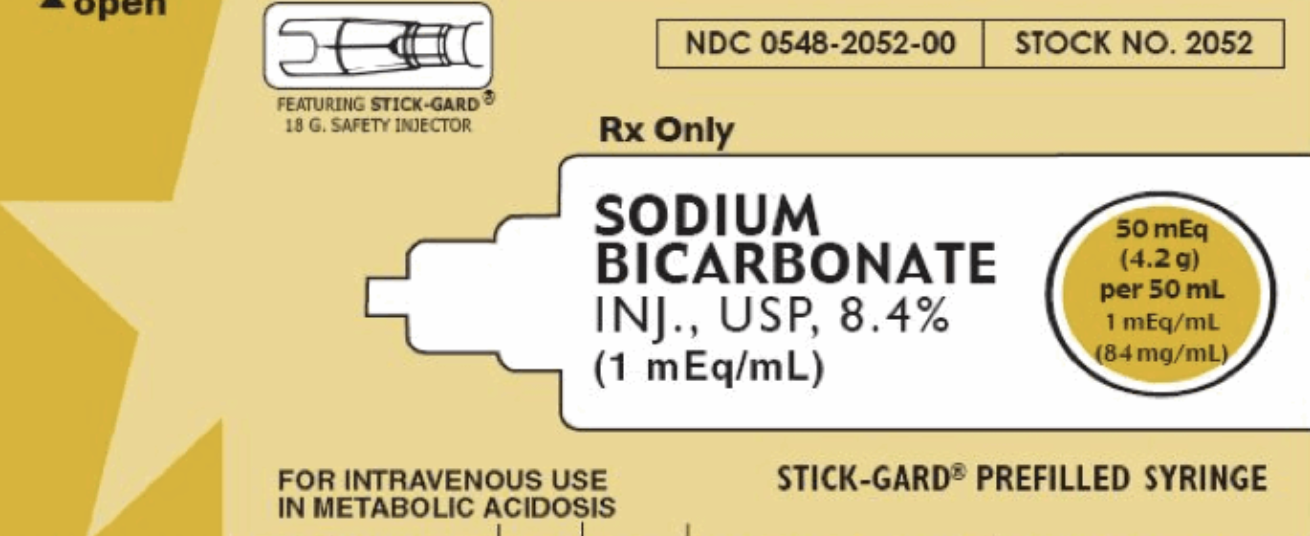

Take a look!

50mL

8.4% NaHCO3 -> 50mEq

The osmolarity of this solution is 2,000mOsm/L - twice that of 3% saline. < (click for emcrit)

Chapter 2: Sodium bicarbonate doesn't just magically raise pH...

Remember this thing?

CO2 + H20 <=> H2CO3 <=> HCO3 + H

It's complicated. Bicarb binds to acid. Then it turns to CO2 and water, so you can breathe it out.

Basically if you're giving bicarb, you can only raise your pH as long as you can breathe off your CO2, increasing your RATE or VOLUME.

**This is particularly a problem in patients who are not in control of their breathing (vented), aren't breathing (arrest), or who have maximized the efficiency of their breathing (Kussmal breathing in DKA).**

That's right - you need to increase your minute ventilation to have a change in pH.

Chapter 3: Sodium bicarb amps can cause harm!

FIRST:

One amp of bicarb is like giving 100cc of 3% hypertonic saline!! But as Josh Farkas points out, we typically have no hesitation giving "a couple of amps of bicarb."

This is a huge osmotic load which can lead to huge fluid shifts - prepare for that amp to increase intravascular fluid by 1/4 liter with every push. (Is this what you want to give to your renal failure pt? Your heart failure pt?)

SECOND:

You are worsening acidosis.

What? Huh? But I thought...

No. Stop. Shush. You're worsening acidosis.

Remember, you're increasing CO2 - whether you can breathe it off or not, this CO2 rises in but blood BUT ALSO rises in the tissues and may worsen acidosis in these tissues. < (click for litfl.com article)

THIRD:

Be ready to cause hypernatremia - expect a rise of 1mEq Na per amp of bicarb.

FOURTH:

Extravasation can cause tissue necrosis.

FIFTH:

CSF acidosis, hypocalcemia. Increased lactate. (Some may argue that's not a bad thing.)

If you do manage to fix the acidosis, you can overshoot and create an alkalosis and even screw up the oxygen dissociation curve (in a bad way).

Chapter 4: It just doesn't f&$%ing work

Cardiac arrest: it doesn't do anything. No increased survival. and AHA says it should not be given routinely.

Lactic acidosis: There's a whole section on UpToDate - there's minimal research for pH < 7.1 so you can consider it at that point... but otherwise, nah.

DKA: Take it from a nephrologist: In ketoacidosis, it is almost never necessary to give bicarbonate even though the patient is bicarbonate deficient unless renal function is permanently impaired. Therapy with fluids and electrolytes restores extracellular volume and renal blood flow, thus enhancing the renal excretion of acid and regenerating bicarbonate.

Hyperkalemia: Amps of bicarb, even in hyperK emergencies, have not been shown to lower potassium. Click that UpToDate link or listen to Scott Weingart talk about it on EMRAP.

Patients with hyperK should be started on isotonic bicarbonate drips for 4-6hours, a treatment that works better in acidotic patients.

CHAPTER 5: Soooo who gets bicarb?

AMPS:

Bicarb ampules in sodium channel blockade (like TCAs) are, as Dr. Bogoch said yesterday, the cornerstone of therapy

Bicarb ampules may be appropriate to alkalinize urine in certain toxicities

Seizing hyponatremic patients

DRIPS:

Appropriate in hyperK patients who can handle fluid

Appropriate in patients with AKI and pH < 7.2 (BICAR-ICU Trial)

May be appropriate for pH < 7.0 or 7.1, depending on who you talk to...

**If the pH is < 7.1 and you wanna give an amp of bicarb, there isn't enough data to say you're wrong. If it's a last-ditch effort, you might as well.

Other references embedded in text.