Ultrasound-Guided PIV: Tricks of the Trade

That’s right, time to talk about one of my favorite topics ever: the ultrasound-guided PIV!

These are tricks of the trade that I have picked up from our amazing ultrasound faculty at Maimonides as well as concepts I have learned based on trial and error. I hope this guide provides some short-cuts to ultrasound-guided PIV expertise to newer trainees!

Procedure:

Scan the area with a tourniquet up to identify your best candidate vein. Look for the largest, most superficial, and most distal. It should ideally be greater than 3mm in diameter.

Visualize the trajectory of your vessel in both short axis and long axis.

Probe marker should be to YOUR left (the same side as the “Z” indicator at the top of the screen). That way when you move your needle left or right, it will go the same direction on the screen.

As you scan, note nerves and arteries which must be avoided.

The patient/extremity should be positioned such that the vessel is straight, and the probe as upright as possible on the patient’s arm.

Prep with chlorhexidine, prep the probe as well or cover the probe with a tegaderm, use sterile gel (“surgilube”).

Get your angiocath ready. Your go-to is a long 20 gauge. If it’s superficial and big and you are already confident in your PIV skills, you may consider placing a short 18, especially if needed for a CT angio. We don’t stock long 18s at this time but may stock them again in the future; these were an excellent option for larger but deeper vessels.

Find the vessel again in short axis at the point you have chosen to cannulate.

Press the Bx button to drop a guide line down the center of your screen. Position the vessel right in the center of that line.

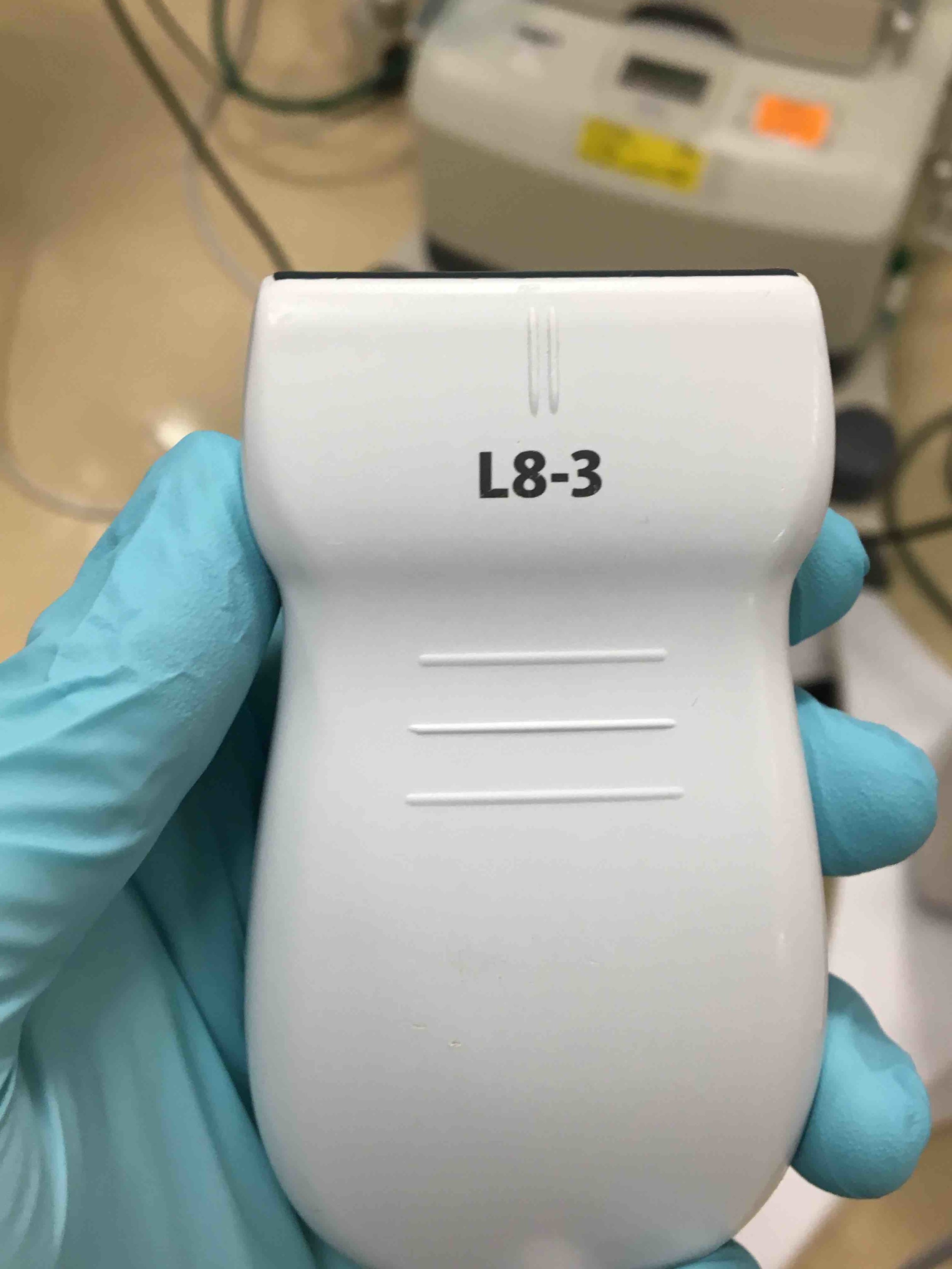

This center line corresponds to the center of the probe:

The “0” on the probe with no notch on it is the center of the probe.

Note how deep the vessel is by looking at the hash marks at the R side of the screen. My vessel above is about 0.75 cm down.

Now keep the probe still and look back at the patient’s arm.

Y

ou know exactly where the vessel is. Right under the center of your probe. You know its trajectory as well. VISUALIZE IT COURSING UNDER THE SKIN. That’s where your angiocath will go.

Now you are ready to enter the skin with your angiocath. Glance up at the screen one more time to make sure your vessel is still perfectly centered on your guide line. Look down at the arm and visualize the vessel again. Enter the skin a little ways back from your probe at a 30-45 degree angle. You know how long your angiocath since you’re looking at it and exactly where the vessel is since you are visualizing it. Using this information,

advance the needle with the aim of positioning your needle tip just over the vessel

, right at the vessel wall. As you do this,

look back up at the screen and you should see your needle tip coming into view

.

Confirm that you’re really seeing the needle tip

: Move the probe back (away from the direction of your needle) and watch the needle tip disappear; move it back toward the needle and watch it come into view again. Do this whenever you have any doubt that you’re actually looking at the tip.

Adjust left/right as needed so that your needle tip is perfectly above the vessel.

Enter the vessel by advancing downward a millimeter.

Sometimes a tiny “jab” will help get through the vessel wall.

Confirm that you’re looking at needle tip again.

You may have flash at this point but don’t look for it; it does not matter.

Drop the angle of your needle at this poin

t. The patient should be positioned so you can effectively drop the angle (arm should be straight if using AC fossa).

Then

advance the probe and needle sequentially millimeter by millimeter

: Advance the probe (needle disappears on the screen), advance the needle (needle tip reappears on the screen), advance the probe again (needle disappears on the screen), advance the needle again (needle tip reappears on the screen), etc.

The needle tip should be centered in the vessel prior to each advancement.

This is demonstrated beautifully by Dr. Cameron Kyle-Sidell in this 4-minute video.

https://emin5.com/2016/04/24/ultrasound-guided-iv-placement/

Once you have “walked” the needle tip into the vessel 5mm or more, keep the needle perfectly still, take the probe off the patient and put it down. Now with your non-dominant hand free, reach over and gently advance the angiocath over the needle while keeping the needle still with your dominant hand. It should advance smoothly.

————

A few last teaching points:

Practice this skill on a model whenever you have a chance.

Use the trick of dropping the Bx line, noting depth, and visualizing the vessel under the skin before starting a central line; if you are good at it with PIVs, you will find this part of central line placement extremely easy.

Needle tip visualization is more difficult with deeper vessels and at steeper needle angles.

If you are more than 1cm deep and have lost your needle tip, you may find it by switching to long axis

Practice the microskill of “twisting” on a vessel in order to convert your short axis to a long axis view; practice this on your own radial artery as often as possible until it becomes second nature.

You can do the entire procedure in long axis. This is a very powerful technique, especially for deeper vessels, but is technically more challenging and requires more practice.

Use regular 22-gauge angiocaths with the “hockey stick” probe for babies and toddlers. If you are comfortable with this by the time you rotate on PICU, they will love you forever.

An US-guided a-line is essentially the same procedure as an US-guided PIV.

Jonas Pologe, PGY3, Emergency Medicine, Maimonides Medical Center